AIDS MEMORIAL

& COMMUNITY MEMORY SITE

VISION

To create an enduring AIDS Memorial & LGBTQ+ Māhū Community Memory Site where current and future generations can

Gather, reflect, mourn, and honor those lost to HIV/AIDS and other forms of oppression and erasure

Uplift Hawaiian traditions of healing, diversity, and inclusion

Celebrate and inspire those working toward a more just, pono future for all.

SITE

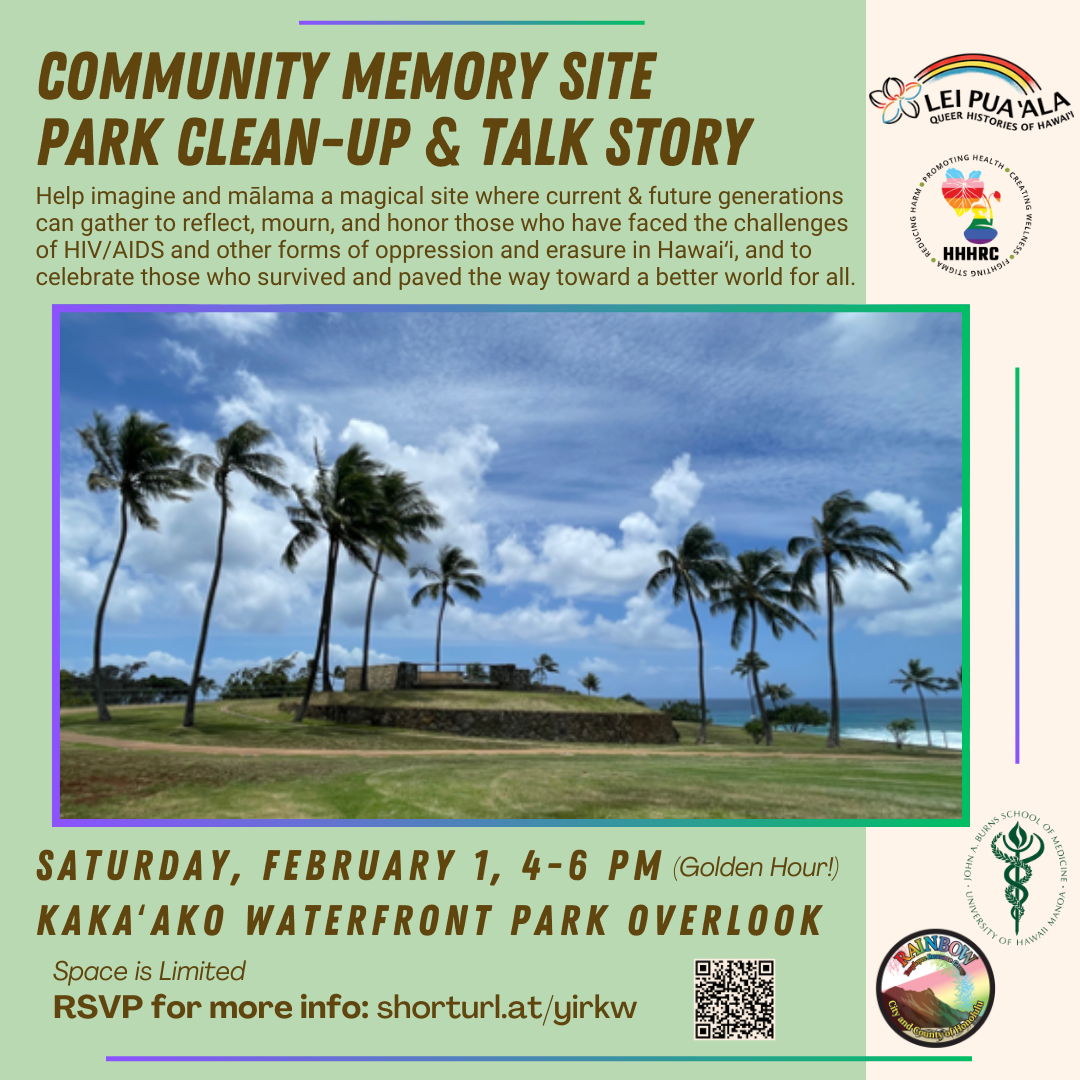

With assistance from the University of Hawaiʻi Community Design Center, and support of the Honolulu Mayor’s Office, the Overlook at Kakaʻako Waterfront Park was selected through a year-long engagement process as the ideal location for the creation of the Hawaiʻi AIDS Memorial & Community Memory Site. With all-encompassing views of city, mountain, and sea, the overlook provides a uniquely spiritual place to gather, heal, hope, and remember.

Kakaʻako also holds historical significance as a place of isolation and quarantine for the successive epidemics of smallpox, Hansenʻs disease, cholera, and bubonic plaque that devasted the Native and immigrant populations of Hawaii throughout the 1800s. In more recent times, with the establishment of the Hawai’i Health and Harm Reduction Center, the John A Burns School of Medicine, and the Papa Ola Lōkahi Native Health organization in the neighborhood, Kakaʻako is becoming a hub for medical care and healing.

In 2024, the Lei Pua ʻAla Hawaiʻi Queer Histories Project and Hawaiʻi Health and Harm Reduction Center partnered with the Honolulu Department of Parks and Recreation on an Adopt A Park agreement to malama the Kakaʻako overlook site. Please contact us or follow our social media if you would like to participate in our next cleanup and talk-story session.

NEED

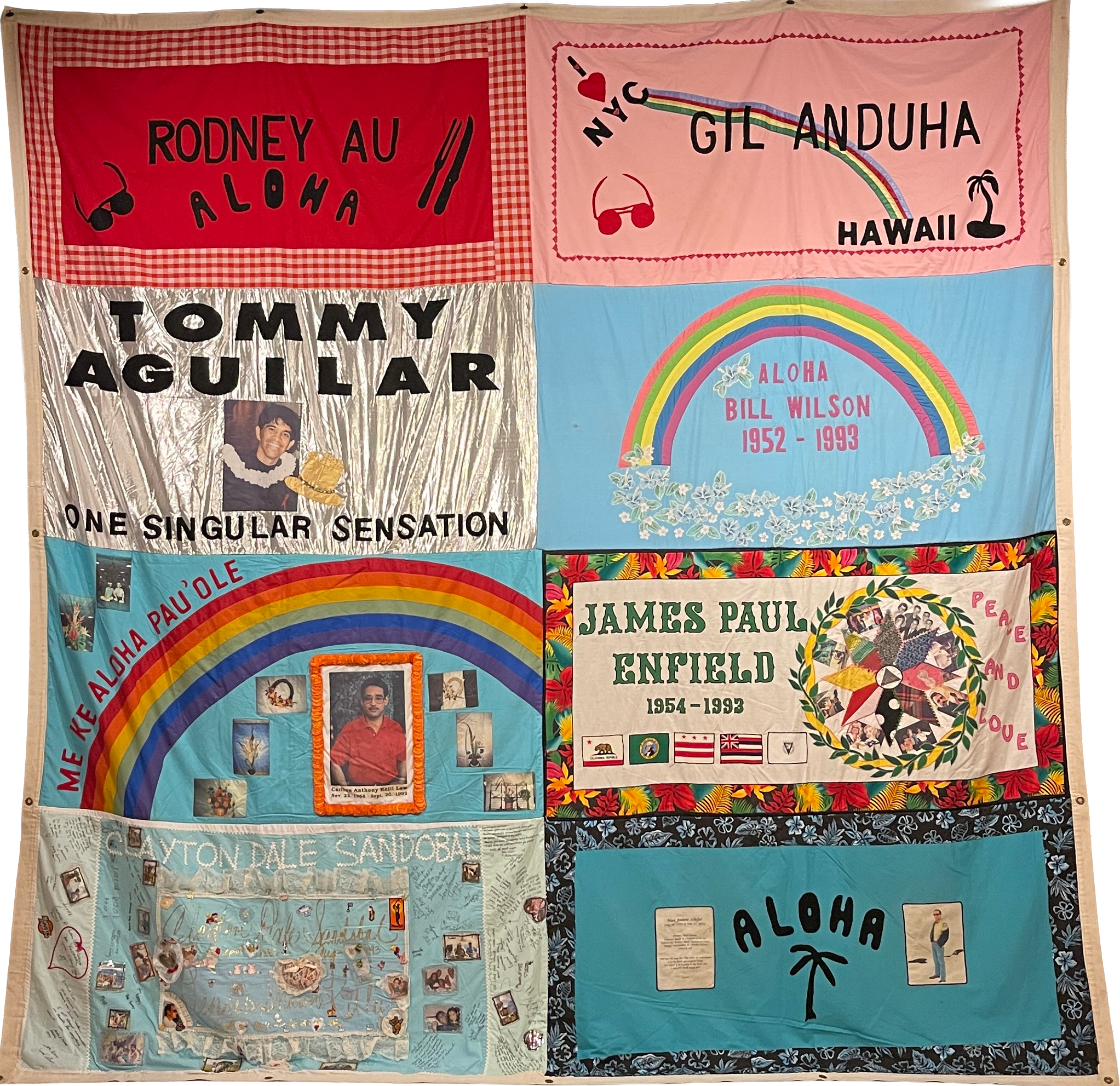

The effort to envision and create a visible and enduring community memory site emerged from a series of talk-stories hosted by Lei Pua ʻAla and Hawaii Health and Harm Reduction Center during the December 2024 display of Hawaiʻi panels from the National AIDS Memorial Quilt at the Capitol Modern. These conversations reflected a long-standing collective desire to ensure that those who were lost or suffered from HIV/AIDS never be forgotten, and that those who loved, cared, and advocated for them always be remembered. Community members stressed that the memorial should emphasize the ways in which Hawai’i, unlike most place in the country, reacted to the epidemic with science, common sense and collective action, an approach that saved many lives and provides a model for effective public health.

PLANNING AND DESIGN

In April 2025, Lei Pua ʻAla Queer Histories of Hawaiʻi and Hawaiʻi Health & Harm Reduction Center teamed-up to initiate a visioning and conceptual design charrette with a broader committee of stakeholders that includes the University of Hawaiʻi Medical School, Hawaiʻi LGBT Legacy Foundation, and other community voices. This group is now working with WCIT Architecture, a Hawaiian Design Firm with extensive experience in Kakaʻako, to refine the design concept toward the goal of construction within two years.

PHASE I CONCEPT DRAWING

PHASE II IDEAS

Honolulu Advertiser, 3/20/34

PARTNERS

HHHRC

MED ZSCHOOL

ERG

CITY AND COUNTY

WCIT

By 1942, Koa Gora found himself back in Honolulu, going by the name “Jake.” He made his living by operating an unlicensed rooming house, “Jakeʻs Place,” a common practice to accommodate the influx of American troops during World War II. The business operated in a Portuguese neighborhood on the slopes of Punchbowl, where it soon attracted the attention of authorities; he was fined $100 (approx. $2,000 today) for hosting a so-called "wild party."

Aerial photograph of Punchbowl, circa late 1940s. The red circle indicates the location of Jake’s Place.

Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 9/20/42

A Fight for Justice

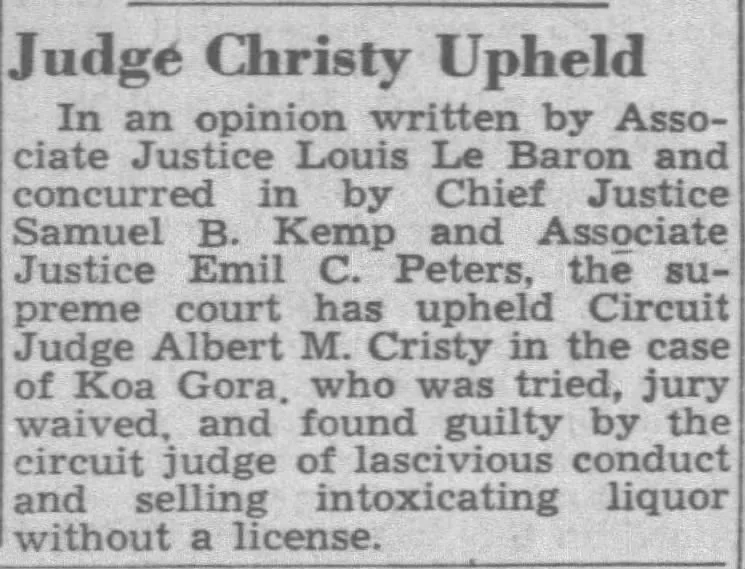

The next year, Jake’s Place became the site of the legal case that brought Koa Gora to lasting attention in the annals of Hawaiʻi’s LGBTQ+ legal history when he was arrested for bootlegging and “attempted indecency.” This time, however, he decided to stand against the charges rather than accept them passively. He appealed the district court's decision to the circuit court, where he was retried but again found guilty of “lascivious conduct,” another term used to describe same-sex interactions.

Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 7/17/43

Determined, Koa escalated his appeal to the Supreme Court of Hawaiʻi. His argument centered not on disputing the facts of the case but rather on the legitimacy of the charges themselves. He contended that the accusations lacked sufficient clarity regarding the nature of the claimed offenses, thus violating his Sixth Amendment rights and denying him the opportunity to properly prepare his defense. His lawyer argued that the statutory language surrounding “lascivious conduct”” invokes the offense as it was known to the common law, namely a public demonstration toward a person of the opposite sex, but because the court failed to state exactly what it was that he actually did, that they couldn’t punish him for it.

The appellate court disagreed, emphasizing that the Hawaiian law referenced “any man or woman who is guilty of lewd conversation, lascivious conduct, or libidinous solicitations,” without regard to whether such was committed in public or in private, or even saying exactly what the accused had done.

Honolulu Advertiser, 9/17/44

Undeterred, Koa Gora pursued his case to the federal judiciary, bringing it before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in 1946. His Hawaiʻi attorneys were Fred Patterson and E.J. Botts, both well-known for their civil rights work including challenging martial law during World War II and defending abortion cases. Their primary argument mirrored that presented in the Hawaiʻi court: the law against "lascivious conduct" was too vague and lacked a clear standard of guilt. They contended that the charges against Gora were inadequately defined, leading to a denial of due process.

In their ruling, the federal judges, for the first time, described what happened on the night of the arrest:

“At about 10:30 a.m., on July 6, 1943, one Arthur Notikai, a shore patrolman with the United States Navy, went to the premises on Kamamalu Street in Honolulu where appellant conducted a rooming house. Notikai, accompanied by a member of the Honolulu Police Department, went there to make an investigation of the place. He entered the premises alone, allegedly looking for a room. Appellant conducted him to a small building on the premises containing a room with shower and toilet. While in this room, appellant unbuttoned Notikai's trousers and laid his hands on his private parts.”

Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit. Koa Gora v. Territory of Hawaii. 1946

The justices had little doubt that this rather modest indecorum was indeed “lascivious conduct,”, which they noted was defined by the Supreme Court as “that form of immorality which has relation to sexual impurity.” They further argued that there was no requirement to be specific because “the indelicacy of the subject forbids it” – a rather remarkable sidestep that emphasizes just how uncomfortable people were with same-sex relations. The reasoning was rooted in “the common sense of the community, as well as the sense of decency, propriety and morality, which most people entertain.” In other words, if the majority thinks something should be illegal, it effectively is.

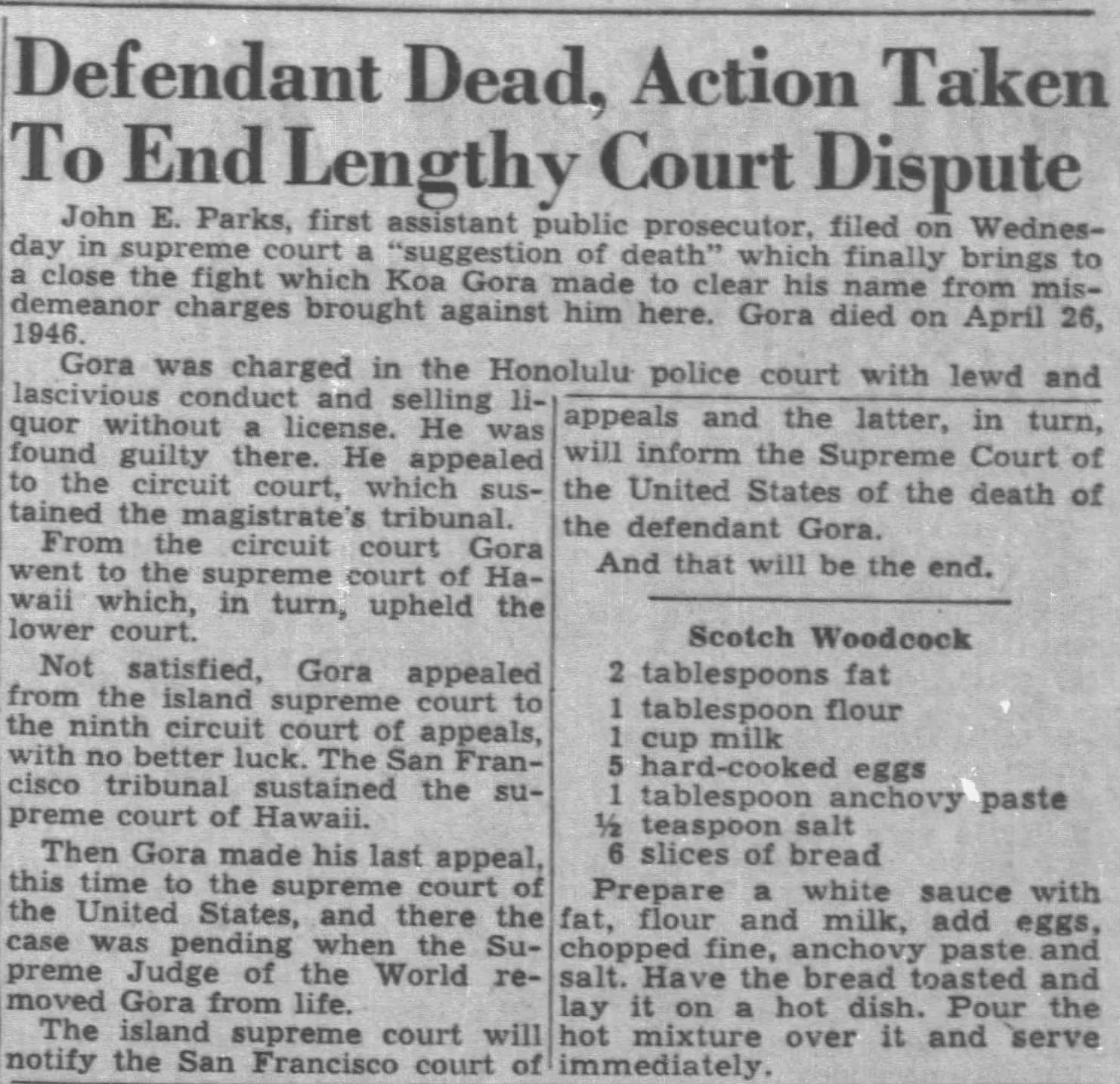

Despite this setback, Gora was not ready to concede defeat. He took the extraordinary step of appealing to the U.S. Supreme Court. Sadly, his fight was cut short when he passed away on April 26, 1946, at the 148th General Hospital in Schofield, Oʻahu. He left behind three married sisters and four brothers, two of whom served as policemen, alongside a customs official and a professional boxer.

Honolulu Advertiser, 7/5/46

Honoring Koa Gora at Puʻuiki Cemetery

Koa Gora was not a gay rights activist in the contemporary sense. He was simply a man demanding a fair trial who wasn’t afraid to publicly challenge the legal system to get it. Although he was unsuccessful in changing the law or its interpretation—a fight that would not conclude until the revision of the Hawaiʻi penal code in 1973—he did make an important contribution: a clear, on-the-record, challenge to a legal and political system that criminalized and brutally punished same-sex desire and relations. It was a rare public refutation in an otherwise compliant social landscape.

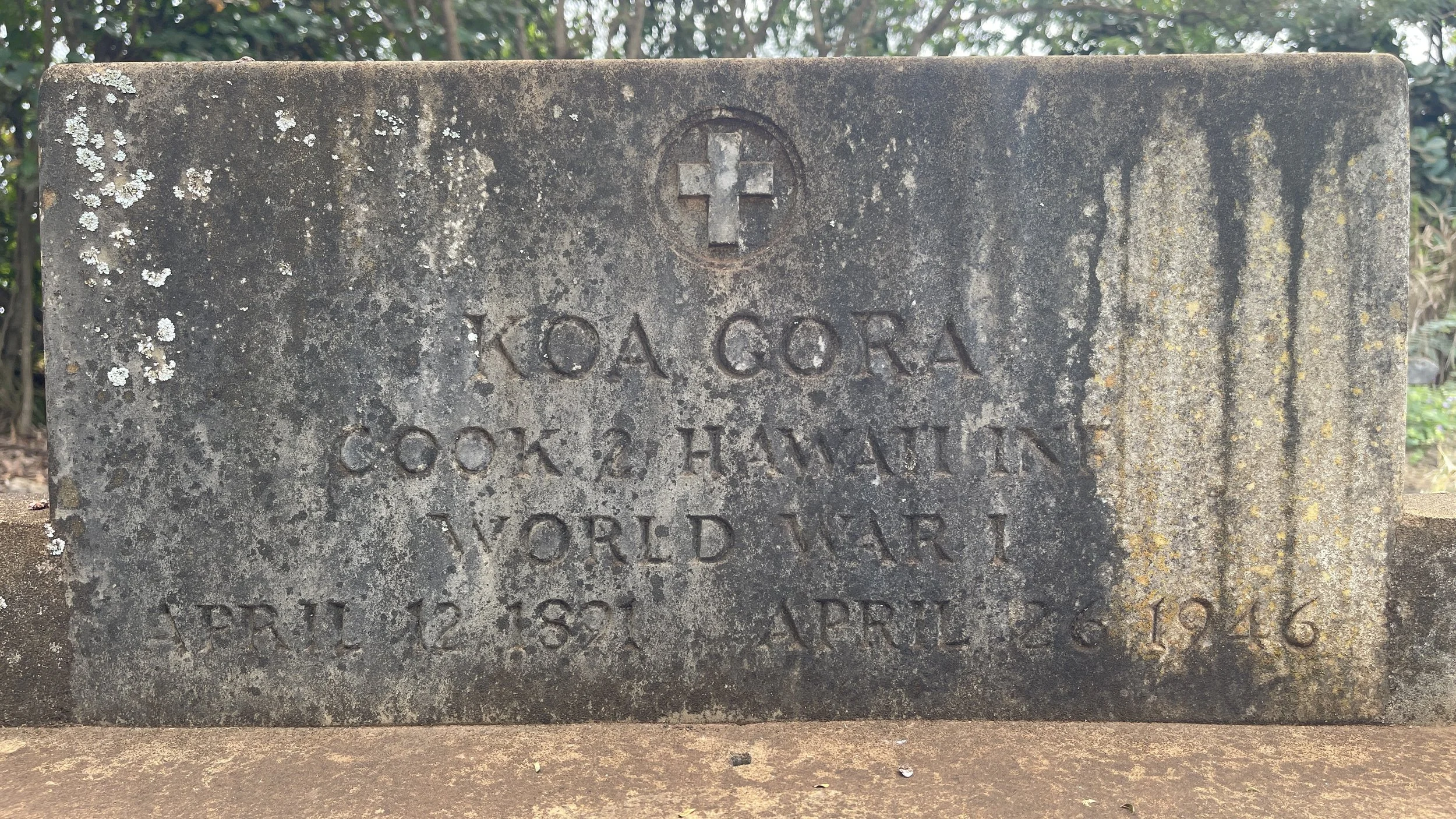

Gora's final resting place is near his childhood home at the Puʻuiki Cemetery in Waialua, in the Portuguese section along with his father and …? His grave is accessible to visitors and serves as a visible testament to his courageous legacy and the ongoing struggle for justice and equality.

Koa Gora’s gravesite and headstone at Puʻuiki Cemetery in Waialua, Oʻahu.

Story by Dean Hamer and Joe Wilson for Lei Pua ʻAla Queer Histories of Hawaiʻi.

Mahalo nui loa to Rose Woods for information about Puʻuiki Cemetery.

Legal Cases:

Supreme Court of the Territory of Hawaii. Territory of Hawaii v. Koa Gora. 37 Haw. 1, decided Sep. 14, 1944.

Circuit Court of Appeals, Ninth Circuit. Koa Gora v. Territory of Hawaii. 152 F.2d 933, decided Jan. 4, 1946

The banner image is an imagined artistic rendering of Jake’s Place in Honolulu’s Punchbowl neighborhood circa 1940.