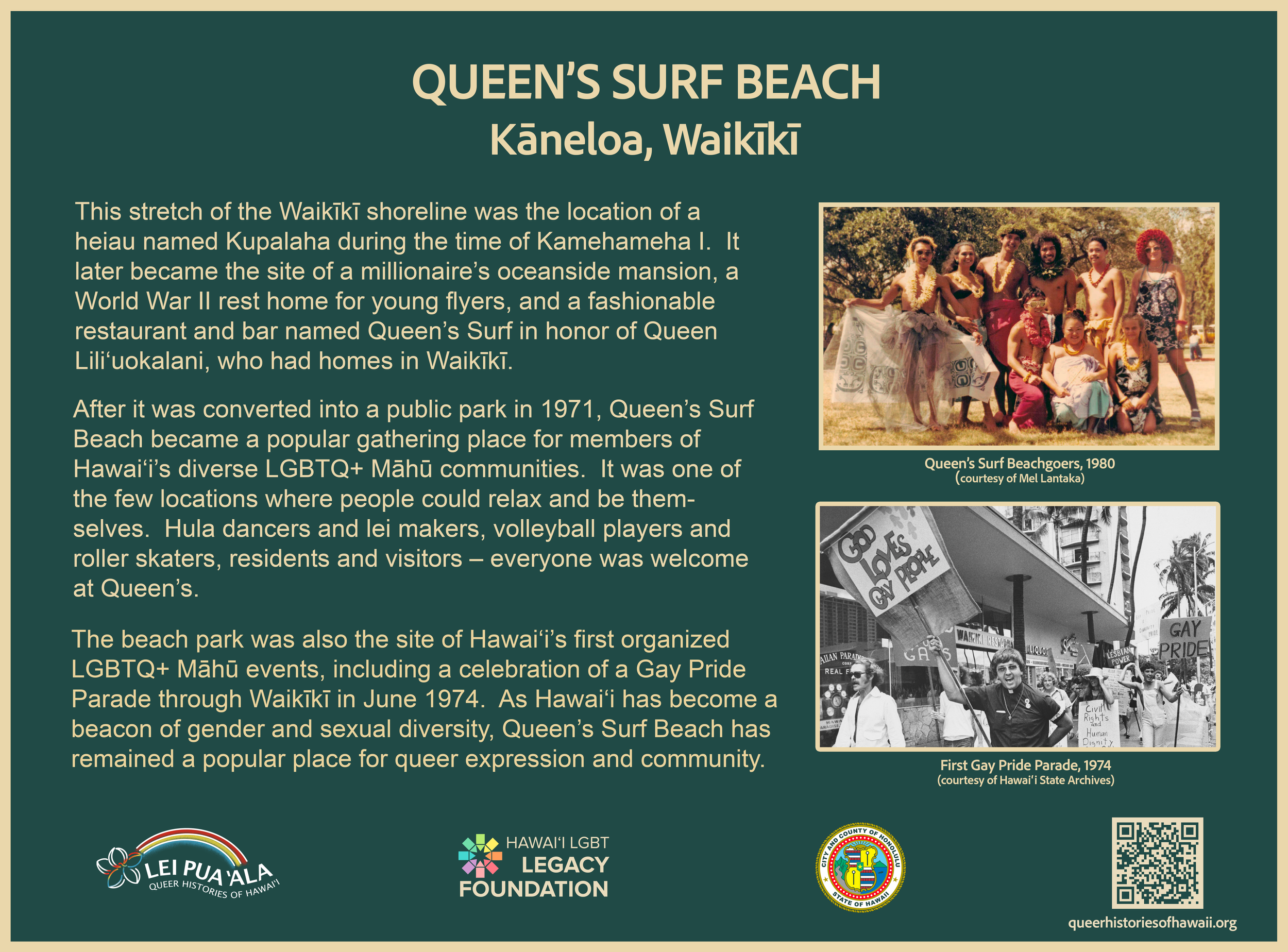

QUEEN’S SURF BEACH

In the 1970s, Queen’s Surf Beach in Honolulu’s Kapiʻolani Park became a popular gathering and organizing space for members of Hawaiʻi’s diverse LGBTQ+ Māhū communities. It was a place where people could relax and be themselves in a society where sexual and gender diversity were just beginning to be openly acknowledged and discussed. Unlike most gay beaches of that era, it was highly visible to the public, emblematic of Hawaiʻi’s relatively accepting environment.

“Queen’s Surf was the place everyone gathered. We would hang out there, people of all ages, a lot of Hawaiian, a lot of mixed cultures there right next to the Natatorium. It was a place where we could just go and be ourselves and everyone was accepted.”

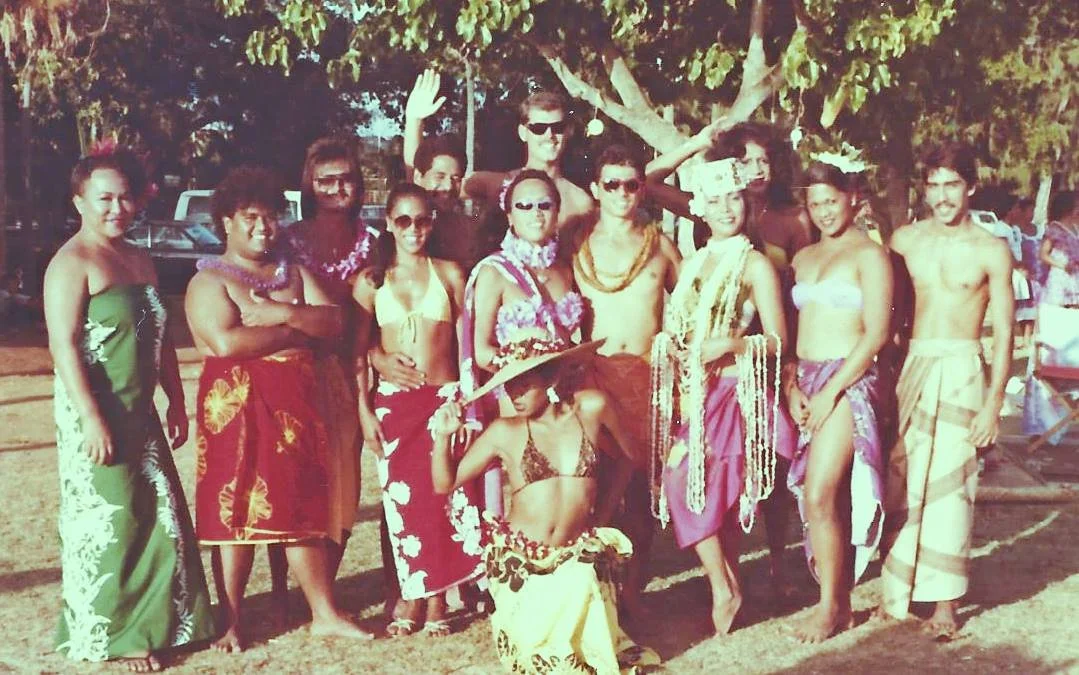

Sina Sison, second from right, with friends. Photo courtesy of Jovann Sarte.

A wide spectrum of people enjoyed the beach. Tourists, including groups of gay men from the continent, often sunbathed on the sand, while locals preferred to relax in the shaded grassy areas. But there were no strict boundaries and many chances to mix and mingle. For young people, the beach was a place to meet without sneaking into a bar or nightclub. For their elders, it was a chance to welcome newcomers and enjoy the company of old friends.

Hula was one of the most popular activities. The Ladies of the Diamond Cattleya, a troupe of māhū dancers associated with the Imperial Sovereign Court of Hawai’i, were admired for their stylish auwana performed in elegant crimson costumes. Robert Cazimero, who formed Hawaiʻi’s first all male hula halau in the early 1970s, often dropped by for an impromptu performance, as did kumu hula-to-be Sonny Ching and dancers from various Waikīkī hotel shows.

Some of the Ladies of Diamond Cattleya. Photo courtesy of Jovann Sarte.

Volleyball was also popular.

“Saturday night, we would play all day into the night, until they shut the lights off. We would sleep down at the beach so that the next morning when we woke up, we could take a shower right there. Brush our teeth and be back on the court.”

Photo courtesy of Mel Lantaka.

Other popular daytime activities included picnicking, card playing, lei making, Hawaiian music, and the annual Miss Queen’s Surf beauty pageant. Evenings were focused on cruising and romance. In 1989, City Councilman Neil Abercrombie proposed that the Queen’s Surf Beach pavilion be converted into “the greatest outdoor gym in the world,” similar to muscle beach in Venice, Ca., but his idea never caught on.

Gay Visibility

Queen’s Surf Beach was also the celebratory site of Hawaiʻi’s first organized LGBTQ+ Māhū event, a “gay parade” held on June 30, 1974, in commemoration of the 1968 Stonewall Revolt in New York. According to a newspaper report, the parade's leaders, “all wearing flowery, violet armbands, held Hawaiian and American flags high on staffs, leading some 25 persons through a sunny Sunday sidewalk crowd in Waikīkī, which appeared mostly amused, sometimes a bit shocked, but very tolerant” in order to “bring to public attention to the need to give gay people full civil rights and end discrimination in jobs and housing and in our laws.”

Photo by David Yamada, Honolulu Advertiser 7/1/74

“What we’re trying to do is show our gay brothers and sisters that they don’t have to be afraid to come out of their closets. We want them to know that Hawaii is a neat place to live – the penal code here is for us, not against us.”

Gay Parade 1974, through Waikīkī to Queen's Surf Beach, led by Grand Marshal Rev. Isbell, at left is Bill Woods. Photo by David Yamada, Honolulu Advertiser 7/1/74

The parade culminated in a pot luck supper celebration at Queen's Surf Beach. In attendance were members of the growing number of queer organizations in Honolulu including Love and Peace Together, Gay Liberation Hawaiʻi, Oahu Bi/Gay Women's Group, Hawaiʻi Council of Gay Organizations, and the Metropolitan Community Church. Although there were no more gay parades until 1990, Pride Picnics at Queen’s Surf Beach became a valued annual event.

Members of The Māhūi, organized by Hawaiʻi LGBT Legacy Foundation, at Queens Surf Beach in October 2024. Photo by Marie Eriel Hobro.

Activity at the beach began to slow down in the late 1980s due to the arrival of HIV/AIDS. This downward trend continued as phone apps replaced traditional cruising, and as queer people became more comfortable being themselves at a variety of beaches. Today, a new generation of queer young people are reclaiming Queen’s Surf Beach as a place of LGBTQ+ Māhū gathering and community through monthly potlucks organized by the Māhūi, a subgroup of the Hawaiʻi LGBT Legacy Foundation.

History and the Mossman Legacy

Queen’s Surf Beach is located in the ʻili of Kāneloa in the ahupuaʻa of Waikīkī. Once occupied by chiefly residences, fertile wetlands, fishponds, and kalo loʻi, it is now defined as the stretch of Kapiolani Park between the Kapahulu Groin and Waikīkī Aquarium. A heiau named Kupulaha was located nearby during the time of Kamehameha I.

1876 map of area what is now Kapiʻolani Park.

Photo courtesy of Images of Old Hawaiʻi.

An elegant seaside mansion was built on the site in 1914 by Mr. and Mr. W. K. Seering of the International Harvester Company, and purchased by Fleischmanʻs Yeast heir C.R. Holmes in 1933. During World War II, it was used as a rest home for young fliers. It was also the site of a 1944 meeting of President Roosevelt with Admirals MacArthur, Nimitz, and Leahy.

Photo courtesy of Images of Old Hawaiʻi.

In 1945 the property was converted into a commercial property that was leased to the Spencecliff Corporation, which operated it as the popular Queen’s Surf Restaurant and Nightclub. Sterling Edwin Kilohana Mossman headlined the nightly shows at the upstairs Barefoot Bar. A detective with the Honolulu Police Department during the day, he was one of Hawaiʻi’s most popular entertainers after dark.

Advertisement, Honolulu Star-Bulletin.

The ”Hula Cop,” as he became known, sang novelty songs, danced the hula, and told jokes in a new style of local comedy. He surrounded himself with a sterling group of entertainers, many of whose footprints lined the stairs to the upstairs bar.

Marking the Spot

The property was condemned by Honolulu Mayor Frank Fasi in 1971 to make way for a public beach. The restaurant and bar were demolished and the beach widened, creating a space that everyone could enjoy.

The Lei Pua ʻAla project, in collaboration with the Hawaiʻi LGBT Legacy Foundation and the City and County of Honolulu, felt that Queen’s Surf Beach deserved an historical marker to honor its role as an important LGBTQ+ Māhū community gathering and organizing space. It was decided to mount the interpretive plaque on a large pohaku (stone), symbolic of the strength and resilience of the queer community.

Keoni Mossman with his wife. Photo courtesy Qwaves LLC.

Fittingly, the skilled mason chosen to create the stone marker is Keoni Mossman – none other than the nephew of entertainer Sterling Mossman. We are proud to have this connection between the past, present, and future of Queen’s Surf Beach as a permanent feature of the Waikīkī landscape.

Note on the name “Queen’s”

The question of why this stretch of shoreline is named Queenʻs Surf Beach has caused considerable confusion.

Several sources state it is because Queen Liliʻuokalaniʻs Waikīkī beach house, Kealohuilani, was located here, but in fact that property is further Eva at Kuhio Beach in the ʻili of Hamohamo, as is also her main Waikīkī residence Paoakalani.

Others believe the beach is named after the Queenʻs Surf surfbreak. But in fact that break is also further Ewa, and the break outside of Queenʻs Surf Beach is named Publics.

Lastly, there is the possibility that the name is a play on the word queen, which is slang for gay or māhū. That would be wonderful!

Gallery of Community Photographs

Summer 1984 - courtesy Mel Lantaka

Christina, Robert Hobdy, Florence Sarte-Castillo and Valeri Keahi-Wong 1985 - courtesy Jovann Sarte

Ricky Silva and Kaulana Kasparovich with others 1985 - courtesy Jovann Sarte

Moses Crabbe, Mel Lantaka, Bill Char and others 1985 - courtesy Jovann Sarte

Summer 1984 - courtesy of Jovann Sarte

Summer 1984 - courtesy of Jovann Sarte

Left to right Kainoa Dela Cruz, Kaleika'apuni Maunakea Brighter, Ned 'Adrian' Nakoa ( miss you braddah), Lot Kahale, Kamuela Ka'Ahanui and Lahela Kaaihue - courtesy Jovann Sarte

Ladies of the Diamond Cattleya - courtesy Jovann Sarte

Ladies of the Diamond Cattleya - courtesy Jovann Sarte

courtesy of Jovann Sarte

courtesy of Jovann Sarte

Puakea Nogelmeier and Bill Char - courtesy of Mel Lantaka

courtesy of Mel Lantaka

Bill Char - courtesy of Mel Lantaka

Sonny Ching (middle) with friends - courtesy Mel Lantaka

Volleyball 1970s - courtesy of Mel Lantaka

Volleyball 1991 - courtesy of Barry G. Porter

Queen's Surf Beach lawn 1991 - courtesy Barry G. Porter

Gay Pride Parade 1974, through Waikiki to Queen's Surf Beach - Honolulu Advertiser 7/1/74

Gay Pride Parade 1974, through Waikiki to Queen's Surf Beach - image by David Yamada, Honolulu Advertiser 7/1/74

Gay Pride Parade 1974, through Waikiki to Queen's Surf Beach, led by Grand Marshal Rev. Isbell, at left is Bill Woods - image by David Yamada, Honolulu Advertiser 7/1/74